- AF Weekly

- Posts

- Rare earth and the US-China powerplay

Rare earth and the US-China powerplay

The heads of the world’s two biggest superpowers will meet next week amidst their high stakes trade war and, among the many items on their agenda, will be a class of minerals that have the potential to wield more power than both countries combined

Graphic by Aarushi Agrawal for Asia Financial

This week, the White House confirmed that US President Donald Trump will meet his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the APEC summit in South Korea at the end of this month. Following the announcement Trump claimed that “everyone’s going to be very happy” after the meeting.

That was a dramatic change in tone for the US president, who had, just two weeks ago, announced the meeting may not happen at all after Beijing decided to significantly tighten restrictions on its exports of rare earths early this month.

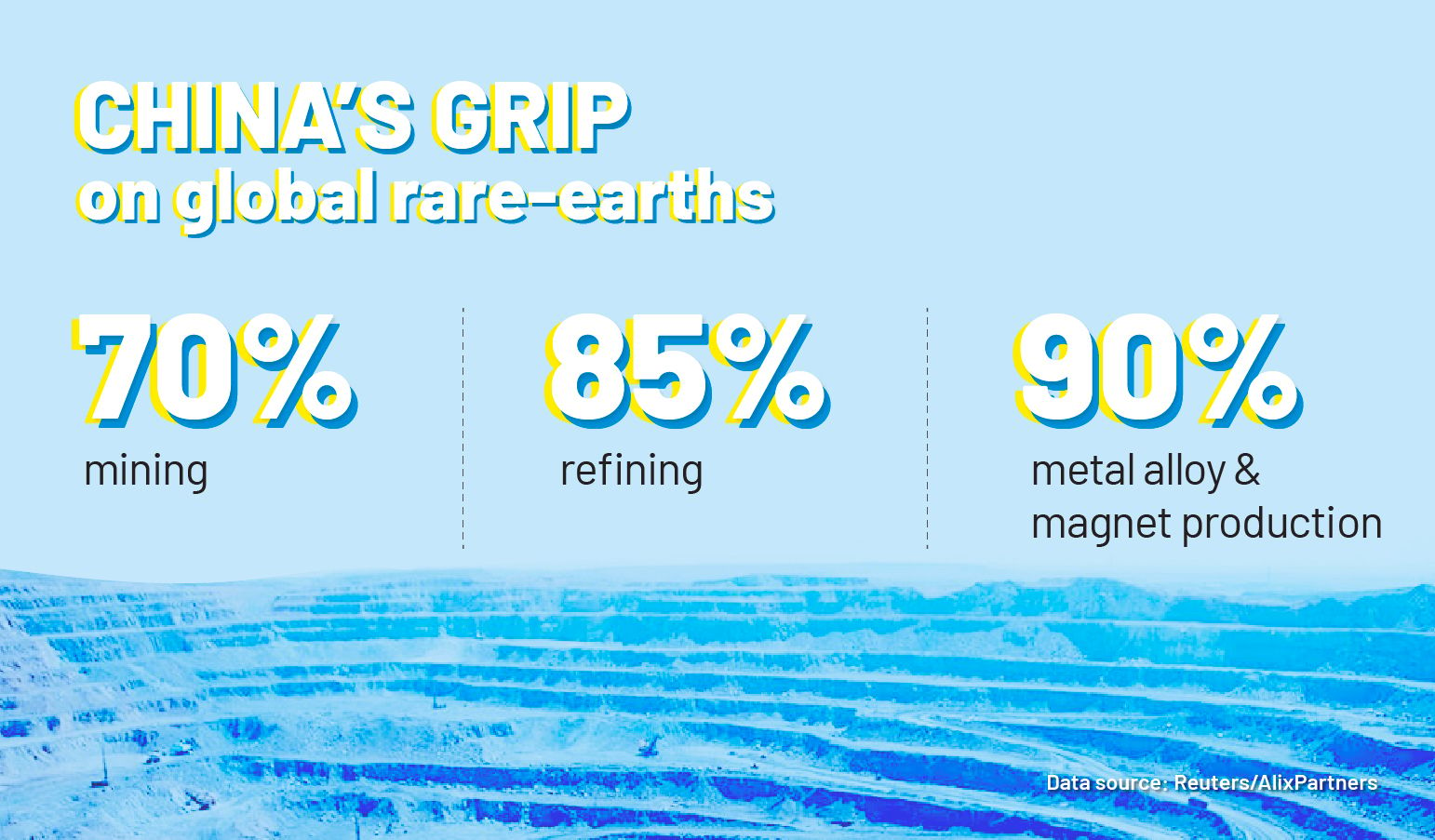

But such is the power of rare earths. This group of 17 elements (with tongue-twisting names) has a profound grip on the world’s most critical industries: be it consumer electronics, military hardware, medical imaging, electric vehicles or other green technologies. And China dominates their processing and refining. The rare earth magnets it creates in the process are just as vital for most modern technologies. "We have millions of these little magnets in every little motor we use — even little motors in our razors,” one expert told Australia’s ABC News, describing their importance.

There are virtually no alternative sources to China for rare earth magnets. And events of the past several months are evidence that Beijing is no longer shy of weaponising that dominance — just as the US weaponised its dominance in the technology behind advanced chips and chipmaking tools. So much so, that China is clearly emulating the American playbook as it steps up its restrictions on rare earths — be it by calling its measures a ‘national security’ interest or setting out rules that will effectively dictate how the vast majority of global firms trade rare earths.

The key difference, though, is that while American chip controls affect just China, Beijing’s export restrictions can actually put critical industries all over the world in crisis. And while China has pushed to become self-sufficient and reduce its reliance on foreign technology for at least half a decade, firms world over have been slow, and even dead in the water, in addressing their critical dependence on Chinese rare earths.

Graphic by Aarushi Agrawal

Take the case of the global auto industry, which was brought to its knees when China first halted rare earth exports in April. At the time, Ford temporarily shut down some production, as did Japan’s Suzuki Motors. Both restarted as China resumed some exports. But six months later, the industry is back to square one. Early this week, Ryan Grimm, Toyota Motor's North America VP of purchasing supplier development, warned: "They can shut us down in two months, the entire auto industry.” Korea’s Hyundai said in June that it had rare earth stockpiles that could last a year. But this week, the carmaker warned most of its inventories “have already been depleted" and that supplies are tight.

Speaking of the impact on the US as a whole, Neha Mukherjee, a rare earths research manager at the consultancy and research firm Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, told Yahoo News: “We are days if not weeks away from a crisis when it comes to national security.”

Such escalation from China, particularly targeting a trade partner as big as the US, has been rare. The first and only instance of China weaponising its rare earth trade — prior to 2023 — was when it cut off rare earth exports to Japan for about two months in 2010. Its more recent curbs, particularly targeting the US, have largely been seen as a retaliation to Washington’s chip export control policies. But none of those measures have been as drastic as the ones China announced this month.

The new rules require foreign companies to get a license from the Chinese government to export products that by value contain 0.1% Chinese-origin heavy rare earths, or are produced using the country's technologies. They restrict other countries from accessing Chinese technology and equipment for mining and processing rare earths to prevent any technology transfers. And they also specifically target advanced chip production. “There is surprisingly explicit language in the controls about this, specifically targeting a number of chips,” Cory Combs, an expert at consultancy Trivium China, told Reuters this week.

That is a dramatic change in Chinese policies with regard to its rare earth trade. According to the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), exporting rare earths from the country was once a “largely routine process” with a fairly straightforward customs clearance process. But the new licensing system that China implemented early this year allows Beijing to decide which companies receive the metals and in what volume. Effectively, China has eliminated any potential for stockpiling — a strategy that had so far shielded global firms from supply disruptions. Some European companies told MERICS that the process has made it completely uncertain when licenses would come through, with delays far longer than China’s promised 45-day window. They also say the process opens the door for Beijing to potentially “gather economic and industrial intelligence” on the firms applying for licenses.

Opinions on China’s larger end goals from these measures vary. A wider consensus is that the new rules aim to give China an undeniable leverage in ongoing trade talks with the US, and particularly ahead of the Trump-Xi summit. “The history of Trump-Xi negotiations suggests that escalation is often followed by tactical truces, and rare earth minerals versus shipping fees could ultimately seal a deal,” UBS analyst Ulrike Hoffmann-Burchardi said in a note referring to the recent tit-for-tat port fees that both countries put in effect this month. The Wall Street Journal also noted that there remains significant ambiguity in the new rules and which products they apply to. That may be “purposeful to give the Chinese side flexibility during negotiations with the US,” it said.

At the same time, there is some speculation that China may not loosen its latest restrictions — or, at least, not too much. Pro-Chinese commentators say the restrictions “simply mirror what the US has been doing to China”. “China’s export control on rare earths is no less non-negotiable than the US’ export curbs on advanced semiconductors and artificial intelligence,” one such commentator wrote in the South China Morning Post, saying Beijing was unlikely to back down from its new rules.

A commentator for The Guardian also noted that Beijing’s dramatic escalation of the trade war was brought on by “the realisation in Beijing that Trump’s reckless America First policies are alienating old and new friends alike, creating a vacuum it can fill.” Beijing’s increasingly abrasive attitude towards the US is also evident from Washington’s admission that not only was it not informed of the new rare earth restrictions, but Beijing also refused to engage with it on the matter. Similarly, early this month, China reportedly asked its newly foe-turned-friend India to provide guarantees that any rare earths it supplies to the country wouldn’t be transshipped to the US.

Wu Xinbo, an expert on ties between the US and China, explained to Reuters: "China believes negotiations alone are insufficient and that effective countermeasures against the United States are necessary to prevent the US from exerting pressure.”

While it remains to be seen whether China has indeed managed to gain an upper hand in negotiations with the US through its new curbs, one thing is clear: countries globally seem to be finally making decisive moves to prevent future instability. Case in point being Trump's deal this week with Australia to invest a combined $3 billion in mining and processing projects Down Under. The White House says US investments in Australia would unlock deposits of critical minerals worth $53 billion.

The move was such a long time coming that ABC News said in one report: “if there is any mystery over America's historic agreement to partner with Australia on the supply of critical minerals, it is why it took so long.”

| In other news, new sanctions imposed by the US on Russia’s two biggest oil producers are set to have a major impact on importers in both India and China. |

| Meanwhile, Sanae Takaichi was elected Japan’s first female prime minister this week and is likely to take the country on a more right-wing path. |

All images via Reuters |

Asia in the centre — with and without China

The key to China’s incredible dominance in rare earths is its mastery, developed over at least four decades, of the difficult and expensive process of separating and refining rare earths from other dissolved minerals after they are mined. Experts say separating heavy rare earths “is the most critical bottleneck” in the production process, and requires complex and specialised technology, infrastructure and raw materials. The expertise means that buyers keep coming back to China, despite risks of dependence, for cheaper rare earths and magnets.

Furthermore, creating a genuine supply chain separate from China is still far from becoming a reality. "In general in the rare earths industry nothing can happen quickly... We might have supply growth in 5-7 years," one analyst told Reuters after the US-Australia rare earths deal. "The time frame for various projects to be ready even for 2027 would be heroic, and unachievable in the case of many projects," he added.

Similarly, Adam Handley, executive chair of Australian rare earth developer Northern Minerals — one of the companies benefitting from the US-Aussie deal — told The Australian Financial Review that “the challenges in getting all these projects up don’t disappear overnight”. “Pricing mechanisms don’t change overnight,” he added. An “extraordinary amount of work” had gone into the US-Australia deal, Handley said, but added that it would have a “lasting impact on the sector”.

And if global countries and companies truly do commit to establishing supply chains independent of China, Asia will play a key role in those plans. Just two days before the Australia-US deal, for instance, Australian Strategic Materials raised $55 million to expand its metals plant in South Korea. Meanwhile, early this month, Pakistan delivered its first-ever shipment of rare earths and critical minerals to the US, following a secretive deal signed last month with an American company to explore and develop its mineral resources. Two heavy rare earths restricted by Chinese export controls — neodymium and praseodymium — were part of the shipment.

Central Asia is also quickly gaining global attention for its potential to supply rare earths. According to The Hague Research Institute, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan collectively hold vast deposits of rare earths that are yet to be explored or mined. These countries are quickly moving “from the margins to the core”, the institute noted.

Malaysia, meanwhile, is also courting miners from across the world to mine its vast rare earth deposits, believed to be worth more than $200 billion. Australia’s Lynas Rare Earths already operates the world's largest single rare earths processing plant in the country. And China is also in talks with the country to process its rare earths. Kuala Lumpur is hosting an ASEAN summit next week — which Trump is set to attend — and plans to leverage ongoing tensions to pitch itself as a key destination for global rare earth supply chains.

Japan, which recently discovered vast deposits of rare earths off the coast of a remote isle, is also planning to begin mining the seabed starting next year. It aims to begin supplying rare earths by 2028.

And India is looking to become another key rare earth player. It holds the world's fifth-largest reserves of rare earths. Currently, the country accounts for less than 1% of global rare earths production but New Delhi has plans to expand its ability by increasing its mining and processing capacity and setting up dedicated manufacturing parks. In July, it reportedly put together a near $840 million plan to produce rare earth magnets. It is also pushing to recycle e-waste to recover critical minerals. Experts say India can work with countries from Africa, Indo-Pacific and South America to develop the technologies it would require to meet those goals.

In northern India, engineers are fast-tracking tests on an electric vehicle motor that could potentially work without requiring any rare-earth magnets. The technology is not new — carmakers like BMW and Nissan are already building EV motors that do not rely on rare earths. But it requires more work to match the efficiency and performance of rare earth magnet-based motors. And while their overseas peers haven’t had much success, these engineers and their backers say they are determined to find a breakthrough even if China eases its export controls.

"This could happen again in five years.”

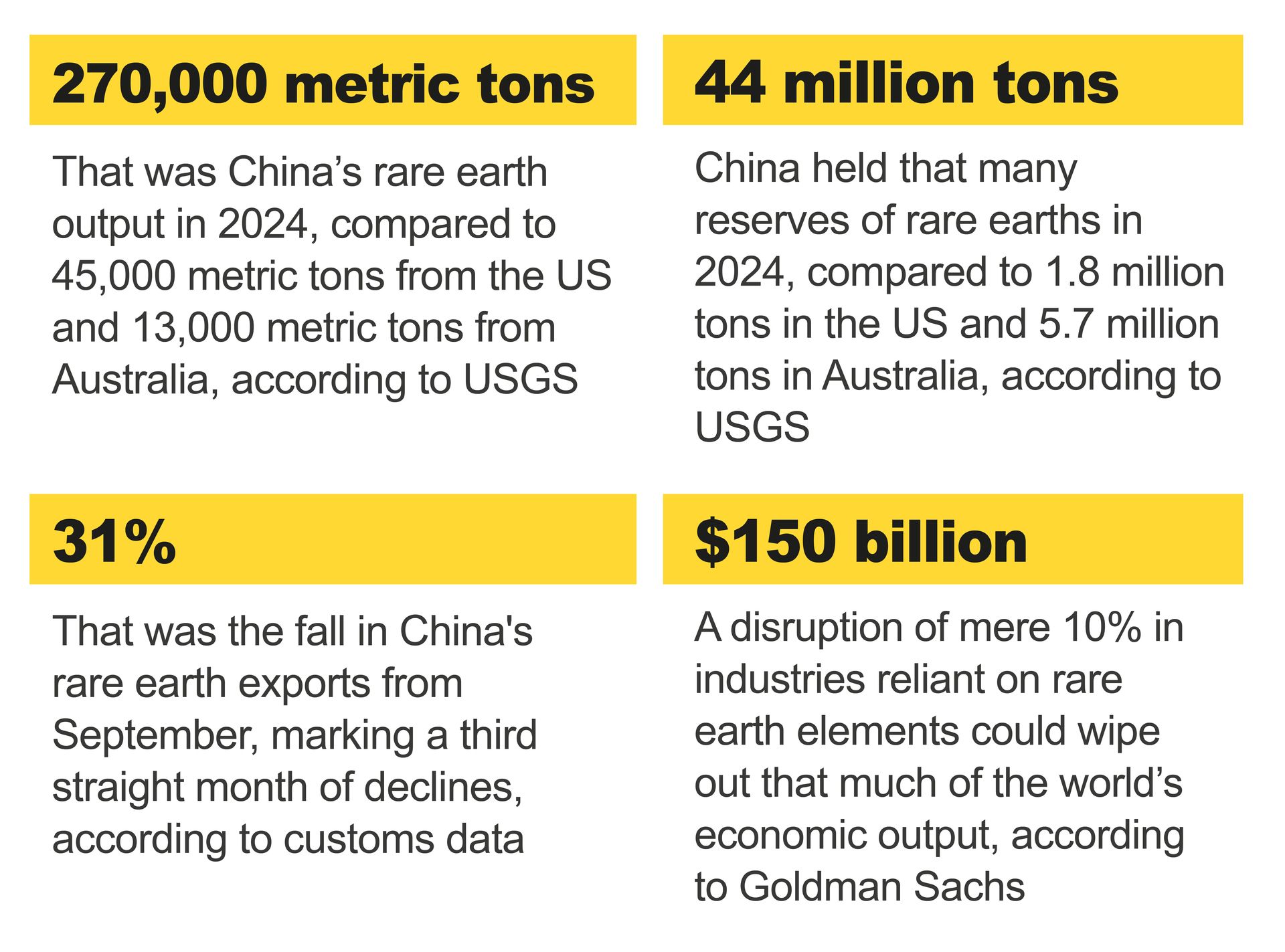

Key Numbers 💣️

Sustain-It 🌿

On to some climate news, the United Nations said in a report this week that almost 90% of the methane leaks detected by satellites around the Earth — and flagged to governments and oil and gas companies — had not been acknowledged. The report said it had documented 25 instances where a notification led to a large emissions event being fixed. But overall, out of 3,500 alerts about methane leaks detected across the oil and gas sector this year only 12% got a response. Methane is the biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. Despite staying in the atmosphere for a shorter time than carbon dioxide, it is much more effective at trapping heat. As a result, scientists consider cutting methane emissions to be the fastest way to tackle climate change in the near-term.

The Big Quote

"Even if the US and all its allies make processing rare earths a national project, I would say that it will take at least five years to catch up with China."

Also On Our Radar

Some of Southeast Asia’s biggest leaders are converging in Kuala Lumpur this weekend for the ASEAN summit but all eyes will be on the outcome of trade talks between US and Chinese officials meeting there.

The heads of China’s Communist Party have said they will increase government investment for people’s livelihoods over the next five years, while also prioritising tech innovation.

Japan’s new premier Sanae Takaichi is set to meets US President Donald Trump next week with plans to buy US pickups, soybeans and gas.

And China said it grew 4.8% in the third quarter, with healthy industrial growth, but analysts say the country’s domestic slowdown makes its economy seriously unbalanced.