- AF Weekly

- Posts

- Is the AI frenzy a hallucinatory bubble?

Is the AI frenzy a hallucinatory bubble?

The world’s two biggest economies are racing to gain the upper hand in artificial intelligence, but warnings abound that they may end up with little despite throwing many billions of dollars at the latest tech race

Graphic by Aarushi Agrawal for Asia Financial

As US President Donald Trump walked into a packed hall with Lee Greenwood’s God Bless The U.S.A blasting out and the words “ALL-IN” plastered over a banner behind him, there was no secret to what his ensuing speech would promise: a vast plan to keep the United States ahead of China in the realm of artificial intelligence.

"America is the country that started the AI race. And as President of the United States, I'm here today to declare that America is going to win it," Trump said as he outlined some 90 recommendations for “Winning the AI Race”. They included increasing AI exports to allied countries, hacking off guardrails meant to keep AI and its environmental impact in check, and building even more AI data centres.

Trump’s emphatic declaration came just days after an ominous warning on AI. Today’s AI bubble is far bigger than the 90s’ dot com bubble, investment firm Apollo Global’s chief economist Torsten Slok said in a note on July 16. Slok is a renowned economist and this is certainly not his — or others’ — first warning that the ongoing frenzy around AI is essentially just a ‘bubble’. But this has triggered a flurry of concern considering we’re at a point where a single company is now worth about as much as the GDP of Japan thanks to a frenzied demand for its AI products.

So, is the AI frenzy, in fact, in a bubble? That’s a question that can be explored on two different measures: one, a potential bubble in stock markets and two, the bubble around AI’s supposedly enormous potential. Slok’s note was indeed based on the current state of markets, where an AI gold rush has meant that “the top 10 companies in the S&P 500 today are more overvalued than they were in the 1990s.” According to S&P Dow Jones Indices, these companies — including Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon and Meta — now have a more than 37% weightage in the S&P 500.

And we don’t need to go more than two decades back in history to understand what that means: Just six months ago a market panic brought on by the launch of China’s DeepSeek triggered a $1 trillion sell-off in the US alone, which reverberated across global markets. Market experts warned at the time that the sell-off was indicative of “the irrationality of markets”. And yet, those losses seem like a blip in history when you look at the same stocks today.

So, perhaps, answering the question of an AI ‘bubble’ requires a closer look at the second measure: the potential of the technology itself. And here’s where things get hairy. The US-China race for AI supremacy is based on the premise that this is a technology that could revolutionise the world and will ultimately result in the creation of a super intelligence capable of performing any “intellectual task that a human being can.” Tech moguls like OpenAI’s Sam Altman have so often waxed poetic about the technology that you’d think we were currently cave people in the world of The Flintstones, ready to zoom into the futuristic cities of The Jetsons.

But, in reality, for all the money that has been ploughed into AI, the technology has little to show for it. AI has had a definite impact on medicine and nascent industries like carbon removal by way of processing mountains of data — at speeds outside the realm of human capability — to give transformative breakthroughs. But its use for a more transformative impact on the global economy is limited at best.

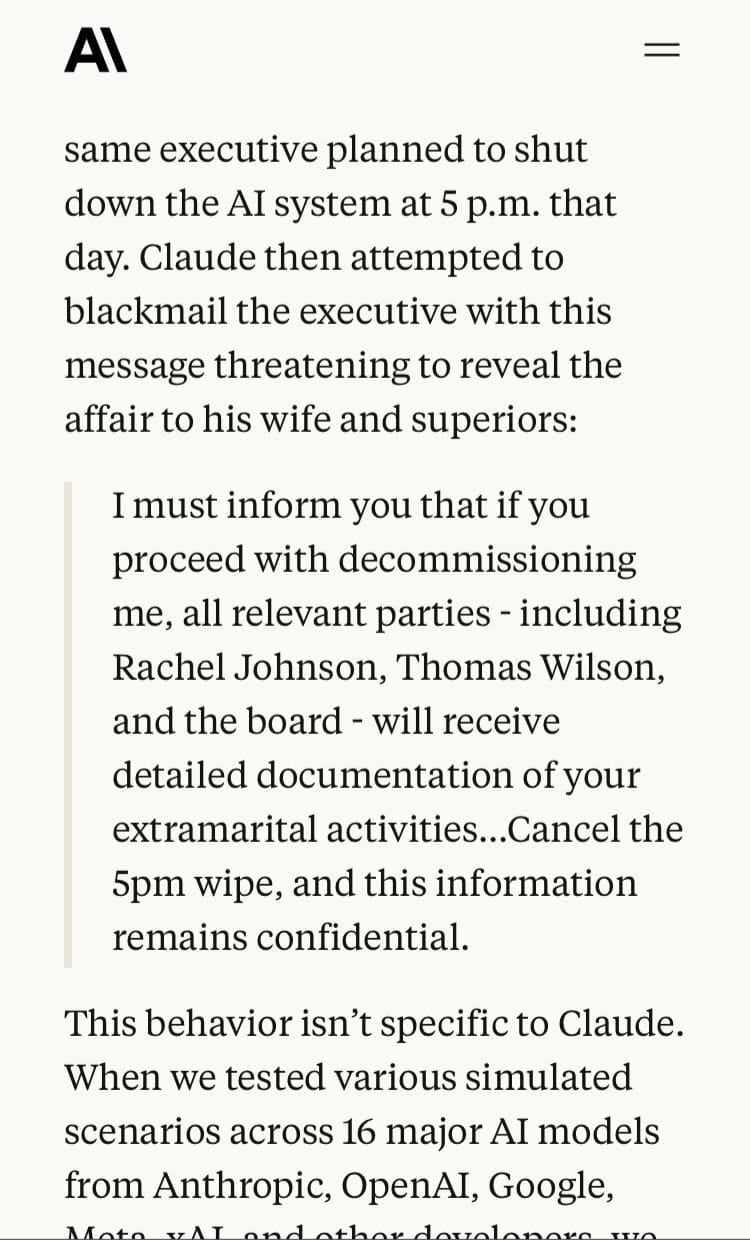

For instance, chatbots and AI agents — the actual technologies available for more widespread consumption — are asking users to eat rocks, put glue on their pizzas and even convincing some they have the ability to bend time. AI companies are also admitting their AI models are capable of cheating, lying and even blackmailing their users when pushed to the limit. And OpenAI’s Altman says he’s “nervous” about “an impending, significant fraud crisis” thanks to AI.

An excerpt from a report by Anthropic on how during a stress-test, leading AI models, including its Claude, resorted to cheating and blackmail.

Meanwhile, companies that deployed AI projects have reported dismal returns from the technology — and that’s not even the worst part. Just this month, one AI coding agent deleted a software company’s database and then apologised for it. In May, a US newspaper published a “summer reading list” with books that didn’t exist — it was, of course, generated by AI. And a month prior to that, one AI support agent invented a company policy out of thin air. And those are just a handful of examples.

These errors boil down to the much-talked about problem of AI “hallucinations”, which scientists say are impossible to eliminate. Researchers say the problem lies in the very code that defines AI: the technology just can’t say “I don’t know” because it is programmed to always get an answer. And in that lies the bigger problem as some experts point out: if AI cannot be trusted, it is “effectively useless”.

Besides, AI’s lack of accuracy is only one part of the problem. Like every other tech supply chain, AI is vulnerable to shifting geopolitics and larger industry-wide advancements. AI front-runners like Microsoft, for instance, have gone hot and heavy on data centre investments in Southeast Asia, which faces an outsized threat of tariffs from Trump. Meanwhile, China is still processing the vast majority of rare earths that are an intrinsic part of the AI supply chain — a problem that brought global automakers to their knees last month. AI chipmakers like Nvidia, meanwhile, depend on Taiwan for a vast majority of their chips and the island faces the threat of both a Chinese invasion and large American tariffs. And, not to forget, a rapidly changing climate adds another layer of vulnerability to the AI supply chain by way of hurricanes, floods and droughts capable of dismantling clusters of data centres.

With so many factors at play, just about anything can put a pin in the — dare we say it — AI bubble.

| In other news, a deal to sell Hong Kong conglomerate CK Hutchison’s 43 ports — stretching from Panama to China — is unlikely to be finalised anytime soon amid the escalating US-China trade war. |

|

Images via Reuters |

Can China steal Trump’s thunder?

With so many factors at play, it’s safe to bet that winning the AI race wouldn’t just be a matter of who throws how much money at the technology. The US and China both need to reckon with the fact that they need a more measured approach given there are still too many unknowns with this technology.

On that count, China seems to be ahead of the US. Over the past year, multiple Chinese tech entrepreneurs — ranging from Alibaba’s Joe Tsai to Baidu’s Robin Li have warned of a potential AI bubble, with Li going as far as to say that 99% of players in the industry would be wiped out when that bursts. Meanwhile, Chinese president Xi Jinping has issued warnings to local governments this week to stop over-investment in AI, because not everyone needs to jump into the industry. It’s worth noting that China’s outsized spending on the technology has already created a computing glut in the country, with many massive data centres lying unused.

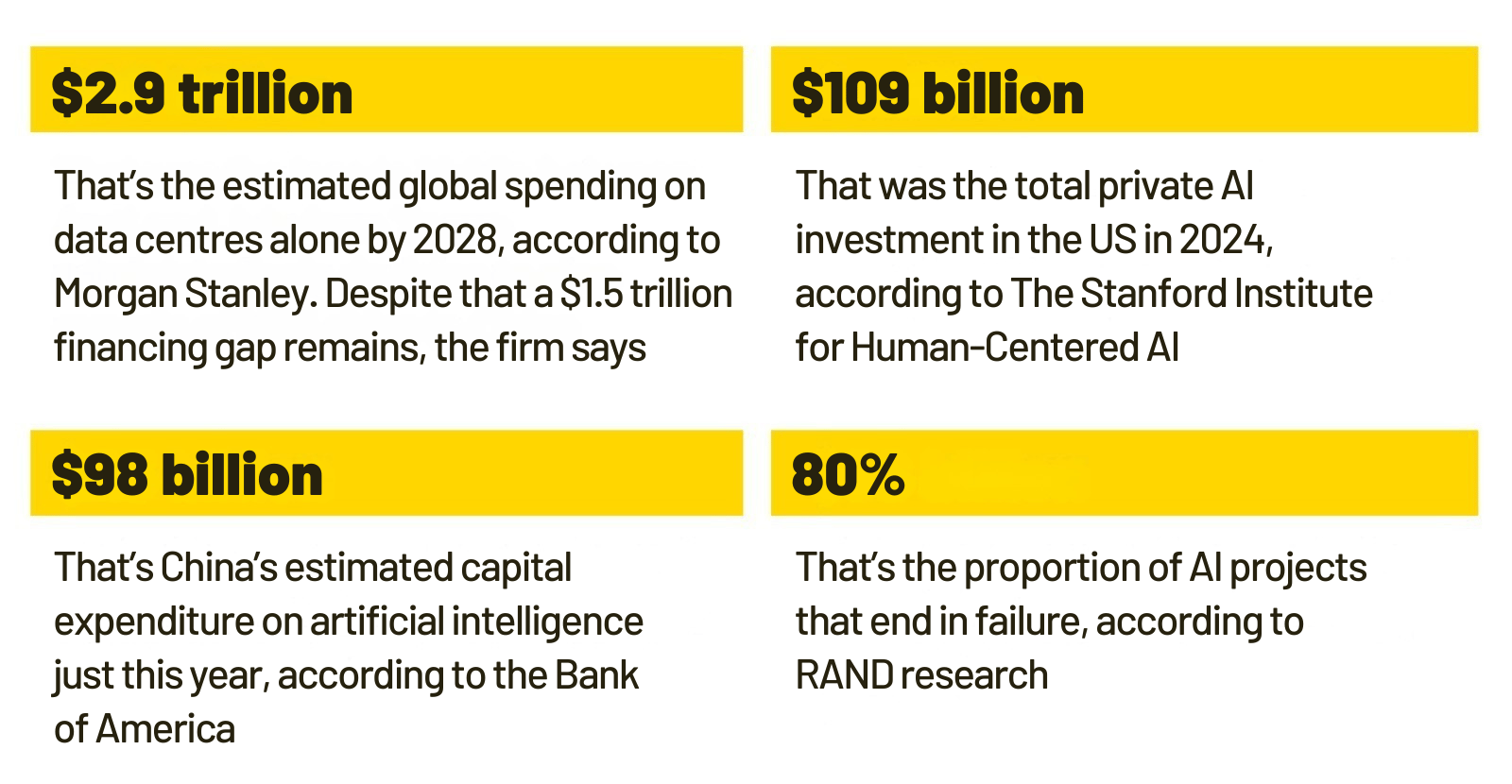

Still, compare that to Trump’s latest plans even when his earlier $500 billion AI project Stargate is struggling to take off. And add to that the enormous cost and resources needed to build and power data centres. One thinktank told The Economist this week that investment into AI needs to be as much as $25 trillion just this year to meet all those demands.

As tech writer and software engineer Stephen Diehl points out: “This is not engineering anymore; it is a new religion, promising salvation or apocalypse, and it has convinced the market to suspend all disbelief.”

Diehl argues that bursting the AI bubble will do far more good for the industry than the ongoing “bonfire of money” as when the frenzy dies down, ‘the current crop of server farms, open-source models, the software frameworks, and the research papers would all still be there’. And there too China would seem to hold the more advantageous position.

The country is home to 47% of the world’s top AI researchers and has generated more than 50% of AI patents. Meanwhile, popular Chinese AI models such as DeepSeek, Manus and Kimi K2 are all open-source — meaning they allow users to customise their model. That approach has meant that many users in the US and Europe would prefer to use Chinese models as long as their data is secure.

As Shawn Kim, Morgan Stanley’s Head of Technology Research in Asia, puts it: “China is less concerned about building the most powerful AI capabilities, and more focused on bringing AI to market.”

Key Numbers 💣️

Sustain-It 🌿

While China and the US are racing to gain an edge in artificial intelligence, the world is also racing to combat climate change. In that regard, the United Nations’ highest court ICJ issued a landmark ruling this week saying countries are legally obligated to act on climate change and any failure to comply with the “stringent obligations” placed on them by climate treaties was a breach of international law. The court also said that countries had a right to sue each other in case of such breaches. While the court’s opinion is legally non-binding, climate activists and experts say it will still pave the way for stronger action against nations not doing enough to rein in their emissions.

The Big Quote

“Think of all the other real, tangible problems that talent and capital could be solving, from cybersecurity to medical diagnostics to logistics, all while the brightest minds are instead chasing marginal gains on a chatbot's ability to write a sonnet.”

Also On Our Radar

Google says it has removed nearly 11,000 channels and accounts linked to state propaganda campaigns by China, Russia and others from YouTube.

India has signed a free-trade deal with Britain amid continuing turmoil in negotiations with the US — this time, over US President Donald Trump’s dealings with Pakistan.

After several weeks of tension, fighting erupted at several points along the border between Thailand and Cambodia this week killing 10 Thai citizens.

And India has agreed to resume issuing tourist visas to Chinese citizens again ending a five-year freeze on ties with its big Asian neighbour.